paranoia and sexuality

in the novels of David Goodis

While David Goodis's novels have provided film-makers with source material for almost fifty years, the novels themselves are only intermittently in print. Geoffrey O'Brien remarks:

Only long after Goodis's death in obscurity

as a portion of his work once again made available to American readers, and its continued availability is by no means a sure thing (O'Brien, p. 88)

Goodis, dubbed 'poet of the losers' (O'Brien, p. 90) is, with Jim Thompson and Cornell Woolrich, among the most significant of the so-called 'noir' writers of the American cold war era. Serpent's Tail are reissuing two of Goodis's novels, so British readers will be able to find Goodis in print again. Read 'em and weep.

Goodis's first novel, Retreat from Oblivion, was published by Dutton in 1939. Writing may have offered Goodis a retreat from oblivion or may have allowed him to wallow in it. He wrote air-stories for the war-pulps during the war years, stories with titles like 'Sky-Coffins for Nazis' and 'Doom for the Hawks of Nippon'. Goodis also wrote for the detective pulps and possibly the horror pulps, both under his own name and under a variety of pseudonyms; he wrote for radio too, including the Superman and House of Mystery series.

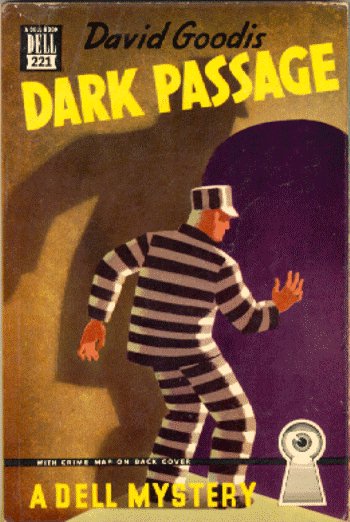

Goodis's second novel was the highly acclaimed Dark Passage, which was first published as a hardback by Messner in 1946. Goodis sold the serial rights to the novel to The Saturday Evening Post; then Warner Brothers bought the film rights and, in 1947, made a successful film under the same title, starring Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall.

Dark Passage has a hard-to-beat opening line that sets the tone of the novel and sums up the anxiety of the era, expressed through so many of the films and novels of cold war America:

It was a tough break. Parry was innocent ... The jury decided he was guilty. The judge handed him a life sentence and he was taken to San Quentin. (Dark Passage, p. 1).

This was the high point in Goodis's writing career. Warner Brothers took him on as a scriptwriter and, with James Gunn, he co-wrote the successful 1947 film, The Unfaithful. The same year saw the publication of Nightfall, Goodis's most successful book, described by Geoffrey O'Brien as 'perhaps his most nearly perfect book ... spare, balanced, and inexplicably moving' (O'Brien, p. 91).

Nightfall is typically claustrophobic. James Vanning, an artist, is an amnesiac bedevilled by blackouts and hallucinations. He cannot be sure if he is guilty of robbery and murder. Police psychologist Ben Fraser pretends to help Vanning, but plans to exploit and entrap him as a means of furthering his own career. Vanning is also pursued by crooks who believe he has the proceeds of a robbery. Fraser's relationship with Vanning gives Fraser something of an identity crisis, however, as he begins to worry about how little he knows about people, that 'so many madmen were walking around and fooling people' (Nightfall, p. 79). Vanning, meanwhile, comes to realise that what he fears most is himself. Jacques Tourneur directed the 1956 film Nightfall, with Aldo Ray as Vanning.

Just when everything appeared to be going right however, Goodis and Warner Brothers parted company. Like one of his novel characters, Goodis was doomed to failure. Goodis's behaviour in Hollywood was remarkable, even by tinseltown standards. Despite his healthy income, Goodis slept on someone else's sofa; wore second-hand suits and, apparently while wearing a dressing gown, tried to pass himself off as a Russian prince in exile (Haut, pp. 21-22). He also haunted the LA jazz clubs, to 'search for large black women who were not averse to knocking him around' (Haut, p. 26).

The precise reasons for Goodis's premature departure from Hollywood are not clear. According to Jack Adrian, Goodis was dropped by Warner Brothers (Adrian and Pronzini, p. 277), while Woody Haut suggests he was 'fed up with Hollywood [and] returned to Philadelphia in 1950' (Haut, p. 22). Geoffrey O'Brien is less certain, stating simply: 'it isn't clear whether he quit or was let go' (O'Brien, p. 92).

What is clear though, is that Goodis returned to Philadelphia, moving in with his parents and disabled brother. While living 'as a virtual recluse with his parents' (Adrian and Pronzini, p. 278), he wrought, in as many years, a dozen novels of desparation for the paperback houses Gold Medal and Lion. The first, and most successful of Goodis's paperback originals, is Cassidy's Girl (Gold Medal 1951) which, as Woody Haut notes, sold over a million copies (Haut, p. 9).

Geoffrey O'Brien remarks, 'with the move to paperback originals, the style and content of his books changed drastically' (O'Brien p. 92). Goodis turned from the depths to 'the lower depths', to delineate characters who had fallen from grace: Cassidy, for example, is a three-time loser, who crashes his plane, his bus and, ultimately, his life. Cassidy's Girl (Gold Medal, 1951) is standard Goodis stuff: the narrative of failure. Failed pilot Cassidy is dominated by his buxom wife, Mildred, with whom he is obsessed--and with whom he must fight physically before he can become sexually aroused. Now a failed bus driver, Cassidy has lost his sense of worth and seeks to escape from Mildred (and himself) by running away with Doris, a slightly-built, quiet, dreamy alcoholic. He finally realises the futility of his attempt to escape.

In The Burglar (Lion, 1953) Harbin is a burglar is going nowhere. He has 'adopted' Gladden, the daughter of the man who taught him his trade, and they are trapped in a sexless yet near-incestuous relationship as they occupy brother-sister/father-daughter roles. Harbin sends Gladden away after a bungled robbery; then he meets Della, which makes him realise he needs Gladden: 'the root of everything was this throbbing need to take care of Gladden' (The Burglar, p.86). In their bid to escape, the gang flee to Atlantic City where Harbin and Gladden declare their mutual love. But in a Goodis novel there can be no happy ever after, and Harbin and Gladden are left all at sea.

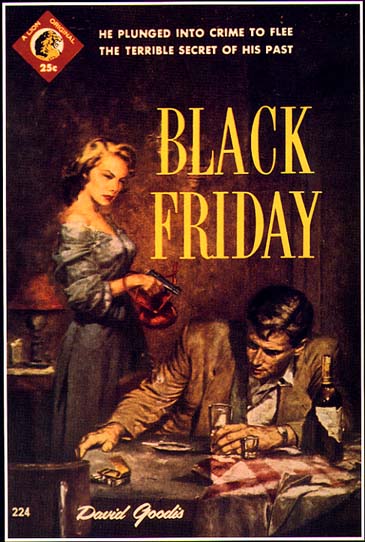

Black Friday (Lion, 1954)

is an 'elaborate variation on The Burglar' (O'Brien, p. 93). It

tells of an artist turned burglar's accomplice, and of how a group of small-time

crooks are bound by their complex relationships. Rene Clement's 1972 film,

And Hope to Die, draws on Black Friday and on Goodis's last

two novels, Raving Beauty (1966) and Somebody's Done For (1967).

Street of No Return (Gold Medal, 1954) opens with three losers on a street corner, wondering where their next drink's coming from. The novel follows the peregrinations of one of them, Whitey, who comes to self-realisation at the end of his journey: losers always lose. 'A wino's odyssey from nowhere to nowhere' (O'Brien, p. 93). The novel was filmed under the same title by Samuel Fuller in 1989.

The Moon in the Gutter (Gold

Medal, 1953) is a tale of unconsumated love and alchoholism set

in the dockland slums of Philadelphia's Vernon Street. Bill Kerrigan's

sister commits suicide with a razor after being raped. Then Kerrigan meets

middle-class Loretta Channing, who comes to Vernon Street looking for excitement.

He cannot bring himself to develop a sexual relationship with her, even

after their ill-matched marriage. His step-sister Bella is the dream girl

with whom he cannot form an emotional bond. Nattassia Kinski played Loretta

in Jean-Jacques Beineix's 1983 film version of The Moon in the Gutter.

The Blonde on the Street Corner (Lion, 1954) tells the story of loafer Ralph Creel. The eponymous blonde is Lenore, the over-sexed sister-in-law of Ralph's simple friend Philip Wilkin, aka Dippy.

He told himself to quit looking at her. She was a married woman who lived here in the neighbourhood. That was one thing. Another thing, she was the sister-in-law of one of his close friends ... From a deeper point of view he was afraid of her. There was something about her that caused his brain to sizzle and he was really afraid of her. (TBotSC, p. 1)

Ralph meets Edna, a shy, 'sort of pale' introvert who is the opposite of the avaricious Lenore. As in Cassidy's Girl, the protagonist finds himself trapped between the physically dominating, sexually demanding woman and the slightly built, quiet, 'dream girl': scared of the physicality of one, he is unable to find the emotional capital required of him by the other. In fumbling, Pinteresque words, Ralph tells Edna he is a songwriter who is 'not really a songwriter' as his attempts to build a relationship crumble. (TBotSC, p. 81)

Set against the familiar backdrop of an impoverished Philadelphia, Goodis's characters are going nowhere, and not particularly fast. They make plans that will come to nothing, anticipating Davies, Aston and Mick in Pinter's The Caretaker by some six years:

Ken sighed: 'Florida's the place. Florida's the only place'.

'When are we going?' Dippy said.

'Any day now,' Ken said.

They sat there looking at the slow-moving curtain of grey smoke as it drifted toward the ceiling and faded away. They lifted their gin glasses and grinned at each other.

(TBotSC, p. 100)

Fear and loathing of female sexuality haunt Goodis's novels. Lenore is depicted as a fat blonde threat to masculinity:'the sound of her high heels clicking on the sidewalk ... was on the order of weird cackling laughter coming at him from all sides, telling him he was trapped' (TBotSC, p. 6); a tease, 'standing in front of the mirror with very little on. Pretending that she did not know that he was watching ... putting her hands on herself ' (TBotSC, p. 107); and a grotesquely gaping, voracious fuck-machine:

She pushed herself against him ... her arms around his middle and she was rubbing herself against him ... He squirmed away from her ... Her face twisted, and her thick-lipsticked lips spread out and then rolled together ... He was shivering now... He was shaking his head, telling himself to get out of here fast. (TBotSC, pp. 108-109)

After a savage fight scene spanning four pages--bringing Goodis's male characters into their closest contact--and which costs Ralph his job, Lenore tries to seduce him:

She was leaning against the dresser, with her hands on her hips. Her lips were wet, and she was sliding her tongue over them again. And then she moved very slowly toward him ... She knew he was scared ... She pulled him down and kept pulling hard and throwing herself up at him. He was still trying to get away. (TBotSC, pp. 138-139)

The planned seduction goes awry as Ralph overpowers Lenore, and Goodis attempts to pass off gynophobic rape as the fulfillment of Lenore's masochistic fantasy:

She became very frightened and breathed fast and hard. Her mouth was open ... He was hurting her now ... And she was gasping ... her entire body quivered, because she was getting it with more force and with more throb than she had ever gotten it before ... she started to moan ... she smiled. Now she had someone who gave it to her like a beast. (TBotSC, pp. 139-140)

Ralph, finally ensnared by the spider-woman, has a vision of the dream girl he knows now will never come: 'For an instant he saw [Edna] clearly, then gradually she faded, like something floating out of a dream. He opened his eyes and saw the fat blonde on the sofa.' (TBotSC p.155)

Goodis is not the greatest stylist of the hardboiled-noir axis of popular American fiction and, as Geoffrey O'Brien remarks, 'there was undoubtedly more promise at the outset of his career than accomplishment at the end' (O'Brien p. 88). But, while the novels are not a particularly pleasant read--and it is something of a truism to note that Goodis is 'more adept at recycling characters with paranoid tendencies-sexual anxiety, obsessive behaviour and criminality--than depicting memorable individuals and storylines' (Haut, p. 22), Goodis's novels are interesting for what they reveal of the collective American psyche in the cold war era; 'they represent an America unsure of its future' (Haut, p. 34), and one is struck by how different is Goodis's America from that of, say, the self-assured 1980s consumer-culture represented in the designer-obsessed fiction of Bret Easton Ellis. As Geoffrey O'Brien observes:

That such testaments of deprivation and anxiety could have sustained a career as a paperback novelist is today cause for wonderment. Nothing so downbeat ... would be likely to find a mass market publisher at present. (O'Brien, p. 94).

David Goodis's novels are fascinating for the way in which the paranoid sexual fears of a wounded individual are crystalised in popular literature as a marketable commodity. While Pinter's plays are 'A'-level set-texts, Goodis's novels are not. Absurd. The Blonde on the Street Corner is re-issued by Serpent's Tail on January 8th, 1998. Serpent's Tail will re-issue The Moon in the Gutter later in the year.

E J M Duggan

References

Jack Adrian and Bill Pronzini, eds, Hard-boiled: An Anthology of American Crime Stories (Oxford University Press: Oxford and New York, 1995). Contains the Goodis short story, 'Black Pudding' (1953).

Woody Haut, Pulp Culture: Hardboiled Fiction and the Cold War (Serpent's Tail: London and New York, 1995).

Geoffrey O'Brien, Hardboiled America: Lurid Paperbacks and the Masters of Noir Expanded edition (Da Capo Press: New York, 1997).